| Timeline | Grave | Gallery |

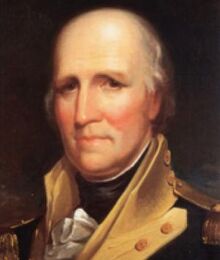

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752 – February 13, 1818) was an American surveyor, soldier, and militia officer from Virginia who became the highest ranking American military officer on the northwestern frontier during the American Revolutionary War. He served as leader of the militia in Kentucky (then part of Virginia) throughout much of the war. He is best known for his celebrated captures of Kaskaskia (1778) and Vincennes (1779) during the Illinois Campaign, which greatly weakened British influence in the Northwest Territory. The British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, and Clark has often been hailed as the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest".

Clark's major military achievements occurred before his thirtieth birthday. Afterwards, he led militia in the opening engagements of the Northwest Indian War but was accused of being drunk on duty. He was disgraced and forced to resign, despite his demand for a formal investigation into the accusations. He left Kentucky to live on the Indiana frontier but was never fully reimbursed by Virginia for his wartime expenditures. He spent the final decades of his life evading creditors and living in increasing poverty and obscurity. He was involved in two failed attempts to open the Spanish-controlled Mississippi River to American traffic. He became an invalid after suffering a stroke and the amputation of his right leg. He was aided in his final years by family members, including his younger brother William, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He died of a stroke on February 13, 1818.

George Rogers Clark was born on November 19, 1752 in Albemarle County, Virginia, near Charlottesville, the hometown of Thomas Jefferson. He was the second of 10 children of John and Ann Rogers Clark, who were Anglicans of English and Scots ancestry. Five of their six sons became officers during the American Revolutionary War. Their youngest son William was too young to fight in the war, but he later became famous as a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The family moved from the Virginia frontier to Caroline County, Virginia around 1756, after the outbreak of the French and Indian War, and lived on a 400-acre plantation that later grew to include more than 2,000 acres.

Clark had little formal education. He lived with his grandfather so that he could receive a common education at Donald Robertson's school with James Madison and John Taylor of Caroline. He was also tutored at home, as was usual for Virginian planters' children of the period. His grandfather trained him to be a surveyor.

In 1771 at age 19, Clark left his home on his first surveying trip into western Virginia. In 1772, he made his first trip into Kentucky via the Ohio River at Pittsburgh and spent the next two years surveying the Kanawha River region, as well as learning about the area's natural history and customs of the Indians who lived there. In the meantime, thousands of settlers were entering the area as a result of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1768.

Clark's military career began in 1774, when he served as a captain in the Virginia militia. He was preparing to lead an expedition of 90 men down the Ohio River when hostilities broke out between the Shawnee and settlers on the Kanawha frontier that eventually culminated in Lord Dunmore's War. Most of Kentucky was not inhabited by Indians, although several tribes used the area for hunting. Tribes were angry in the Ohio country who had not been party to the treaty signed with the Cherokee, because the Kentucky hunting grounds had been ceded to Great Britain without their approval. As a result, they tried to push the American settlers to out of the area, but were unsuccessful. Clark spent a few months surveying in Kentucky, as well as assisting in organizing Kentucky as a county for Virginia prior to the American Revolutionary War.

As the American Revolutionary War began in the East, Kentucky's settlers became involved in a dispute about the region's sovereignty. Richard Henderson, a judge and land speculator from North Carolina, had purchased much of Kentucky from the Cherokee in an illegal treaty. Henderson intended to create a proprietary colony known as Transylvania, but many Kentucky settlers did not recognize Transylvania's authority over them. In June 1776, these settlers selected Clark and John Gabriel Jones to deliver a petition to the Virginia General Assembly, asking Virginia to formally extend its boundaries to include Kentucky.

Clark and Jones traveled the Wilderness Road to Williamsburg where they convinced Governor Patrick Henry to create Kentucky County, Virginia. Clark was given 500lb of gunpowder to help defend the settlements and was appointed a major in the Kentucky County militia. He was just 24 years old, but older settlers looked to him as a leader, such as Daniel Boone, Benjamin Logan, and Leonard Helm.

In 1777, the Revolutionary War intensified in Kentucky. British lieutenant governor Henry Hamilton armed his Indian allies from his headquarters at Fort Detroit, encouraging them to wage war on the Kentucky settlers in hopes of reclaiming the region as their hunting ground. The Continental Army could spare no men for an invasion in the northwest or for the defense of Kentucky, which was left entirely to the local population. Clark spent several months defending settlements against the Indian raiders as a leader in the Kentucky County militia, while developing his plan for a long-distance strike against the British. His strategy involved seizing British outposts north of the Ohio River to destroy British influence among their Indian allies.

In December 1777, Clark presented his plan to Virginia's Governor Patrick Henry, and he asked for permission to lead a secret expedition to capture the British-held villages at Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in the Illinois country. Governor Henry commissioned him as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia militia and authorized him to raise troops for the expedition. Clark and his officers recruited volunteers from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina. The men gathered in early May near the Falls of the Ohio, south of Fort Pitt. The regiment spent about a month along the Ohio River preparing for its secret mission. Patrick Henry had been a leading land speculator before the Revolution in lands west of the Appalachians where Virginians had sought control from the Indians, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River at Fort Massac and marched to Kaskaskia, capturing it on the night of July 4 without firing their weapons. The next day, Captain Joseph Bowman and his company captured Cahokia in a similar fashion without firing a shot. The garrison at Vincennes along the Wabash River surrendered to Clark in August. Several other villages and British forts were subsequently captured, after most of the French-speaking and Indian inhabitants refused to take up arms on behalf of the British. To counter Clark's advance, Hamilton recaptured the garrison at Vincennes, which the British called Fort Sackville, with a small force in December 1778.

Prior to initiating a march on Fort Detroit, Clark used his own resources and borrowed from his friends to continue his campaign after the initial appropriation had been depleted from the Virginia legislature. He re-enlisted some of his troops and recruited additional men to join him. Hamilton waited for spring to begin a campaign to retake the forts at Kaskaskia and Cahokia, but Clark planned another surprise attack on Fork Sackville at Vincennes. He left Kaskaskia on February 6, 1779 with about 170 men, beginning an arduous overland trek, encountering melting snow, ice, and cold rain along the journey. They arrived at Vincennes on February 23 and launched a surprise attack on Fort Sackville. Hamilton surrendered the garrison on February 25 and was captured in the process. The winter expedition was Clark's most significant military achievement and became the basis of his reputation as an early American military hero.

News of Clark's victory reached General George Washington, and his success was celebrated and was used to encourage the alliance with France. General Washington recognized that Clark's achievement had been gained without support from the regular army in men or funds. Virginia also capitalized on Clark's success, laying claim to the Old Northwest by calling it Illinois County, Virginia.

Clark's ultimate goal during the Revolutionary War was to seize the British-held fort at Detroit, but he could never recruit enough men and acquire sufficient munitions to make the attempt. Kentucky militiamen generally preferred to defend their homes by staying closer to Kentucky, instead of making a long and potentially perilous expedition to Detroit. Clark returned to the Falls of the Ohio and Louisville, Kentucky, where he continued to defend the Ohio River valley until the end of the war.

In June 1780, a mixed force of British and Indians from the Detroit area invaded Kentucky, including Shawnee, Delaware, and Wyandot, among others. They captured two fortified settlements and seized hundreds of prisoners. In August 1780, Clark led a retaliatory force that won a victory at the Shawnee village of Peckuwe, the present-day site of George Rogers Clark Park near Springfield, Ohio.

In 1781, Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson promoted Clark to brigadier general and gave him command of all the militia in the Kentucky and Illinois counties. As Clark prepared to lead another expedition against the British at their allies in Detroit, General Washington transferred a small group of regulars to assist, but the detachment was disastrously defeated in August 1781 before they could meet up with Clark, ending the campaign.

In August 1782, another British-Indian force defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks. Clark was the militia's senior military officer, but he had not been present at the battle and was severely criticized in the Virginia Council for the disaster. In response, Clark led another expedition into the Ohio country, destroying several Indian villages along the Great Miami River during the Battle of Piqua, the last major expedition of the war.

The importance of Clark's activities during the Revolutionary War has been the subject of much debate among historians. As early as 1779 George Mason called Clark the "Conqueror of the Northwest." Because the British ceded the entire Old Northwest Territory to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1783), some historians, including William Hayden English, credit Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original thirteen colonies when he seized control of the Illinois country during the war. Clark's Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized.[26]

More recent scholarship from historians such as Lowell Harrison have downplayed the importance of the campaign in the peace negotiations and the outcome of the war, arguing that Clark's "conquest" was little more than a temporary occupation. Although the events of the Illinois campaign often describe the harsh, winter ordeal the Americans endured to reach their targets, James Fischer points out that the capture of Kaskaskia and Vincennes may not have been as difficult as previously suggested. Kaskaskia proved to be an easy target; Clark had sent two spies there in June 1777, who reported "an absence of soldiers in the town."

Clark's men easily captured Vincennes and Fort Sackville. Prior to their arrival in 1778, Clark had sent Captain Leonard Helm to Vincennes to gather intelligence. In addition, Father Pierre Gibault, a local priest, helped persuade the town's inhabitants to side with the Americans. Before Clark and his men set out to recapture Vincennes in 1779, Francis Vigo provided Clark with additional information on the town, its surrounding area, and the fort. Clark was already aware of the fort's military strength, poor location (surrounded by houses that could provide cover), and dilapidated condition before his arrival. Clark's strategy of a surprise attack and strong intelligence were critical in catching Hamilton and his men unaware and vulnerable. After hatcheting five captive Indians to death within view of the fort, Clark forced its surrender.

Alcoholism and poor health afflicted Clark during his final years. In 1809 he suffered a severe stroke. When he fell into an operating fireplace, Clark suffered a burn on his right leg that was so severe it had to be amputated. The injury made it impossible for Clark to continue to operate his mill and live independently. As a result, he moved to Locust Grove, a farm eight miles from the growing town of Louisville, and became a member of the household of his sister, Lucy, and brother-in-law, Major William Croghan, a planter.

In 1812 the Virginia General Assembly granted Clark a pension of four hundred dollars per year and finally recognized his services in the Revolutionary War by presenting him with a ceremonial sword.

After another stroke, Clark died at Locust Grove on February 13, 1818; he was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later. Clark's remains were exhumed along with those of his other family members on October 29, 1869, and buried at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

In his funeral oration, Judge John Rowan succinctly summed up Clark's stature and importance during the critical years on the trans-Appalachian frontier: "The mighty oak of the forest has fallen, and now the scrub oaks sprout all around." Clark's career was closely tied to events in the Ohio-Mississippi Valley at a pivotal time when the region was inhabited by numerous Native American tribes and claimed by the British, Spanish, and French, as well as the fledgling U.S. government. As a member of the Virginia militia, and with Virginia's support, Clark's campaign into the Illinois country helped strengthen Virginia's claim on lands in the region as it came under the control of the Americans. Clark's military service in the interior of North America also helped him became an "important source of leadership and information (although not necessarily accurate) on the West."

Clark is best known as a war hero of the Revolutionary War in the West, especially as the leader of the secret expeditionary forces that captured Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in 1778–79. Some historians have suggested that the campaign supported American claims to the Northwest Territory during negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Paris (1783).

Clark's Grant, the large tract of land on the north side of the Ohio River that he received as compensation for his military service, included a large portion of Clark County, Indiana, and portions of Floyd and Scott Counties, as well as the present-day site of Clarksville, Indiana, the first American town laid out in the Northwest Territory (in 1784). Clark served as the first chairman of the Clarksville, Indiana, board of trustees. Clark was unable to retain title to his landholdings. At the end of his life, he was poor, in ill health, and frequently intoxicated.

Several years after Clark's death the state of Virginia granted his estate $30,000 ($568,853 in 2009 chained dollars) as a partial payment on the debts it owed him. The government of Virginia continued to repay Clark for decades; the last payment to his estate was made in 1913.

Clark never married and he kept no account of any romantic relationships, although his family held that he had once been in love with Teresa de Leyba, sister of Don Fernando de Leyba, the lieutenant governor of Spanish Louisiana. Writings from his niece and cousin in the Draper Manuscripts in the archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society attest to their belief in Clark's lifelong disappointment over the failed romance.